Death to the Serotonin Hypothesis April 20, 2007

Posted by Johan in Abnormal Psychology, Neuroscience.trackback

If you’ve ever watched TV in the US, you’re most likely aware that according to a number of ads where sad, lonely people filmed in black-and-white suddenly turn into happy families with children filmed in colour, you feel low because something called serotonin is lacking in your brain, and by taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) you can correct this problem.

This sounds straight-forward enough, but unfortunately, it doesn’t appear to be true. To understand why, let’s start at the beginning.

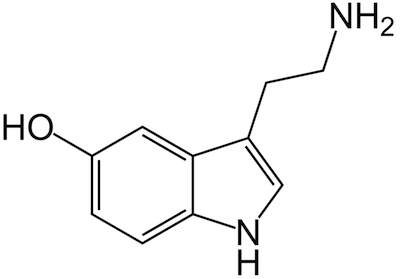

Serotonin is a type of neurotransmitter. Neurotransmitters are chemicals that allow the action potential (ie signal) in one neuron to travel across the synaptic cleft (ie the gap) to the next neuron. According to researchers like Schildkraut and later Coppen, depression is caused by a deficiency in serotonin, which impairs neuronal communication. Presumably, these communication difficulties are expressed as the typical symptoms of depression.

Pharmaceuticals companies have come up with a number of ways to boost serotonin levels. The most popular option of these is the SSRI. This type of medication acts by preventing the normal re-uptake of serotonin that essentially functions as the “off” switch in the synapse. SSRIs don’t cause a complete stop in serotonin re-uptake because if they did, the serotonin would remain in the synaptic cleft indefinitely, causing constant firing of the connected (post-synaptic) neuron. This would probably be a bad thing. Anyway, the point to be made is that SSRIs don’t actually boost serotonin levels, they merely act to ensure that the available serotonin becomes more potent.

So what is the problem with the serotonin hypothesis? A recent open-access paper by Lacasse and Leo (2005) serves as a good primer. Essentially, their point is that the only evidence that exists in favour of the serotonin hypothesis is the alleged efficacy of SSRIs – if they make your serotonin more potent and this improves your condition, the problem must have been in your serotonin levels to begin with, or so the logic goes. This kind of reasoning is logically flawed, and Lacasse and Leo (2005) emphasise this point with a nice example:

the fact that aspirin cures headaches does not prove that headaches are due to low levels of aspirin in the brain. (p. 1212)

Just to be safe, Lacasse and Leo show that even if the efficacy of SSRIs were evidence for the serotonin hypothesis, this evidence may not be all that it’s cracked up to be. A study which gained access to unpublished clinical trials of antidepressants found that when the published and unpublished data were taken together, 80 percent of the antidepressant response was duplicated by the placebo, and perhaps more strikingly, 57 percent of these company-funded trials failed to produce a significant difference between the SSRI and the placebo. In itself, this is unimpressive for any drug, but it is really bad news for the serotonin hypothesis, as the boost in serotonin potency that these drugs produce apparently does little, if anything. It’s hard to see why this intervention should not work, if it really were all down to serotonin levels. Another blow is dealt by the finding that more recent antidepressants that do not specifically affect serotonin levels appear to be as effective as SSRIs.

Despite the general consensus on the problems with the serotonin hypothesis, pharmaceutical companies continue to rely on it when they explain their product to prospective patients. Lacasse and Leo (2005) cite a wealth of examples of this:

“Celexa helps to restore the brain’s chemical balance by increasing the supply of a chemical messenger in the brain called serotonin. Although the brain chemistry of depression is not fully understood, there does exist a growing body of evidence to support the view that people with depression have an imbalance of the brain’s neurotransmitters.” (Citalopram)

“LEXAPRO appears to work by increasing the available supply of serotonin. Here’s how: The naturally occurring chemical serotonin is sent from one nerve cell to the next. The nerve cell picks up the serotonin and sends some of it back to the first nerve cell, similar to a conversation between two people.

In people with depression and anxiety, there is an imbalance of serotonin—too much serotonin is reabsorbed by the first nerve cell, so the next cell does not have enough; as in a conversation, one person might do all the talking and the other person does not get to comment, leading to a communication imbalance.

LEXAPRO blocks the serotonin from going back into the first nerve cell. This increases the amount of serotonin available for the next nerve cell, like a conversation moderator. The blocking action helps balance the supply of serotonin, and communication returns to normal. In this way, LEXAPRO improves symptoms of depression.” (Escitalopram)

“When you’re clinically depressed, one thing that can happen is the level of serotonin (a chemical in your body) may drop. So you may have trouble sleeping. Feel unusually sad or irritable. Find it hard to concentrate. Lose your appetite. Lack energy. Or have trouble feeling pleasure…to help bring serotonin levels closer to normal, the medicine doctors now prescribe most often is Prozac®.” (Fluoxetine)

“Chronic anxiety can be overwhelming. But it can also be overcome…Paxil, the most prescribed medication of its kind for generalized anxiety, works to correct the chemical imbalance believed to cause the disorder.” (Sertraline)

“While the cause is unknown, depression may be related to an imbalance of natural chemicals between nerve cells in the brain. Prescription Zoloft works to correct this imbalance. You just shouldn’t have to feel this way anymore.” (Paroxetine)

I think part of the reason why these companies insist on clinging to the serotonin hypothesis is that it is relatively simple to understand. “You don’t have enough of X, so we give you a drug that boosts X.” You can’t even explain something as basic as paracetamol in such simple terms. Naturally, saying “this seems to help, but we really don’t know why” doesn’t inspire confidence, even though that statement would probably reflect the current scientific consensus.

References

Lacasse, J.R., & Leo, J. (2005). Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific Literature. PLoS Medicine, 2, 1211-1216.

According to Dr. Irving Kirsch in Prevention & Treatment, “there is now unanimous agreement that the mean difference between response to SSRI antidepressant drugs and response to inert placebo is very small. It is so small that, despite sample sizes involving hundreds of participants, 57% of the SSRI trials funded by the pharmaceutical industry failed to show a significant difference between drug and placebo. Most of these negative data were not published and were accessible only by gaining access to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) documents.

Various methods were used to manipulate the results of SSRI drug studies to insure a favorable outcome:

1) Responders to the placebo are eliminated at the beginning of the study. (Placebo washout)

2) Benzodiazepine sedatives were given to mask the SSRI induced agitation.

3) Unfavorable drug studies are buried in the file cabinet and not disclosed to the public.

4) Miscoding suicidal events as “emotional lability”, and homicidal events as “aggression” to hide suicidal events from regulators.

5) False attribution of suicide to the placebo arm.

6) Hiring ghost writers to make the medical articles more favorable.

7) Cash settlements for SSRI drug litigants which seals records and withholds unfavorable drug studies from the public.

For more information and links see my

Paxil, Prozac, and SSRI Induced Suicide Newsletter

Jeffrey Dach MD

Gay Military XXX

Gay Military XXX

Gay Mature XXX

Gay Mature XXX

[…] portrays.” Bullshit! My cynical view of SSRIs has become mainstream. Check out this post, titled “Death to the Serotonin Hypothesis,” which nicely debunks the serotonin-depression hypothesis. Thanks to my old friend Chris Bremser, a […]

[…] work, although it is far from clear why boosting synaptic Serotonin levels should work, given the weak evidence for a lack of Serotonin in depression. With ECT, there are no convincing explanations for either the how or the why. Psychiatrists […]

[…] I posted about the much-maligned serotonin theory of depression and tentatively defended it, while making it clear that “low […]

[…] inhibitor (SSRI) class of anti-depressants, who’s efficacy is now called into question, and likewise the underlying hypothesis. SSRI’s are under-effective, replete with bothersome side effects […]

caviarcreativo.com

Death to the Serotonin Hypothesis | The Phineas Gage Fan Club